Individual Variations in Susceptibility and Spread

Individual Variations in Susceptibility and Spread

The susceptibility to the different kinds of SARS-CoV-2 infections and the individual determinants of transmission are analysed.

entire page in work and needs to be checked.

- Summary

- Relevance

- Observables for Covid Infections

- Viral Load in Epidemiology

- Infector Distribution

- Effects of Movement

- Associations to BMI

- Effects of Dirty Air Exposure

- Transmissions by Age

- Effects of Acquired Immunity

- Overview of Data Sets

- References

- References Spread Children and Schools

- References OUCS

- References SIREN

- Refs Household Transmissions

- Refs Household Transmission Endemic CoVs

- Refs of Household Transmissions with HOSTED

- Refs ONS-CIS Analyses

- Refs Maccabi Healthcare Services

- Refs Cohort Studies

- Refs Cohort Studies in Denmark

- Refs Cohort Studies in Qatar

- Refs Contact Tracing

- References Spread from Sequences

- References Transmission Heterogeneity

- References Acquired Immunity Status

- References Spread and Air Pollution

- Refs Smoking effects on SARS-2 Infections

- Transmission Respiratory Viruses

- References other Viruses

- Appendix

Summary

Most epidemiological analyses specify SARS-CoV-2 infections with the observables typical symptoms and/or a “detectable” viral load in the upper respiratory tract. However sampling the upper respiratory tract is not perfectly predictive for the overall viral load since most SARS-CoV-2 lineages infect cells in the conducting airways. Nevertheless the viral load in the upper respiratory tract is correlated to symptoms. Symptoms are also correlated to the overall viral load. Symptomatic persons (Transmission by Symptom Status) are more likely to transmit Covid. Most (nearly all?) superspreading events described, are caused by symptomatic persons, likely because superspreading involves high numbers of virions in the conducting airways, which usually causes symptoms.

How much a person contribute to the spread of SARS-CoV-2 is highly individual. Most observations conclude that 20% of the infectees are responsible for at least 80% of the infections (Transmission Distribution). The individual transmission is associated to both biological and social factors. Social factors include the living situation and the behavior. Biological factors influencing susceptibility and infectiousness. These biological factors are discussed in the following.

People with an adequate and sensitive immune system control coronavirus infections early and if at all only mild symptoms are induced. Sometimes there is a high initial viral load localized to the mid or upper respiratory tract, but usually coronaviruses do not replicate to high numbers. Low numbers of coronaviruses don’t cause severe disease and are associated with a low probability of transmission and detection. This theoretical argumentation is supported by the observations:

- People with regular movement are about 30 % less likely to get both mild respiratory diseases including Covid. An even further reduction is observed for severe diseases. A healthy diet helps to maintain a good microbiome in the intestine which is important for the overall immunity.

- Long-time exposure to air pollution, few movement and obesity can reduce the capability of the respiratory tract to handle viruses. Air Pollution und overweight both increase the Covid risk as observations at the individual and at the population level suggest.

- A major determinant how well the body can handle SARS-CoV-2 is age, especially for the initial infection. Young people are less susceptible to get a disease and usually control the viral load timely. Accordingly a lower susceptibility and on ward spread are observed in household settings (Transmission by Age Groups). Few spread is observed between children and in schools. Superspreading with children as index cases is nearly never observed.

The immune system can learn from exposures and induce an improved protection against subsequent similar exposures. This remembering includes the classical acquired immune responses such as T cells and B cells capable to produce antibodies. Additionally infections usually induce a location specific adaptions.

Previous infections provide a reliable and long lasting protection:

- The protection against hospitalization is above 95%.

- The chance to test positive is reduced by 80% or more. The protections is stable across time and mostly across variants. The chance to have a high viral load (Ct value <30) and symptoms is reduced by more than 90% [to confirm].

The muscular administrated ‘mRNA’ and adenovirus vectored vaccines induce mainly a systemic immunity. Accordingly the protection against pneumonia (=severe Covid) is good. On the other hand the protection against infections in the conducting airways or the upper respiratory tract is mediocre and last only a few months. Similarly for transmission.

- Protection against pneumonia and hospitalization: Accordingly to the systemic immunity provided, a good protection against hospitalization: most investigations conclude a reduction of at least 70 % in the first half year after vaccination.

- Protection against infection: In the first few months after vaccination the chance to test positive (the detection limit is usually at 40 PCR cycles which is about 1000 cps/milliliter) is reduced and during this time the probability for high viral loads is even further reduced. The protection gradually decreases and vanishes about 3 to 6 months after vaccination (depends individual factors and SARS-2 variants present). The chance for testing positive after exposure is reduced by about 70% for BNT162b2 in the first 2 months and then gradually decreases and the reduction is lost about 3 to 6 months after vaccination against the delta variant. The ChAdOx1 initially reduces the chances to test positive by about 50%. While ChAdOx1 starts lower than BNT162b2 the decay of protection is slower. The protection from mRNA-1273 starts and stays higher than BNT162b2/ChAd0x1.

- Protection against Transmission: Some studies observe in the phase when the vaccine induced immunity reduces the viral load, a reduced onwards transmission from vaccinated index cases; other studies observe no difference even in this phase. After a few months when the viral load in the tract are the same as for unvaccinated people, there seems to be no reduction, at least in household settings.

The widespread assumption that vaccinated people transmit Covid less for more than a few months lacks a rigorous scientific basis. To my judgement, there is neither an epidemiological nor a medical benefit/basis to (push to) vaccinate people not at risk for severe Covid.

In my opinion, the actions for people with higher R values should always be options to take and never be any restrictions on human rights or any other any restrictions with outcast effects. Further discussed in considerations on increased R value.

Relevance

Knowing how transmissions are distributed, helps to set and fine-tune control measures. If measures are necessary.

- Measures can few for those contributing few to the spread: children and young adults are not the carriers of the Covid spread and thus measures should not target them.

- People with higher R values can be offered control options: E.g. free test access, suitable masks (e.g. custom fit FFP2 including advice on wearing them) and better education how to handle Covid.

Observables for Covid Infections

To analyze susceptibility and transmissions, one needs to specify which the SARS-CoV-2 infections to count and how to diagnose them. Diagnosis is traditionally geared toward diagnosing a disease to possibly initiate a treatment, discussed in the chapter Diagnosis and Viral Load.

Detection of infections for epidemiological investigations is mostly done by:

- Symptoms

- Hospitalizations, Deaths

- Viral load

- Antibody detection for previous infections

For mild diseases the viral load or symptoms are often used as observables for epidemiological investigations. Similarly the viral load is often used to determine the possibility of transmissions. In the case of severe disease the variables of main interest, hospitalizations and deaths, are observable themselves. Additionally hospitalization is a good proxy for severe disease.

Association between Viral Load and Symptoms

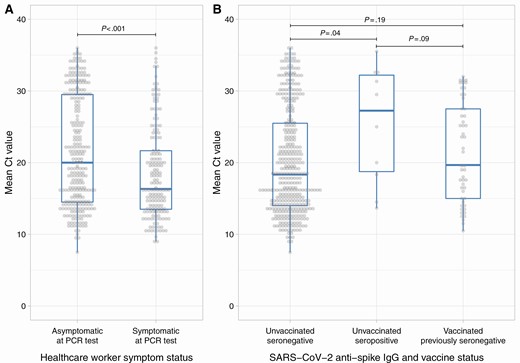

- Lumley et al observe for the viral loads taken by nasal and oropharyngeal swabs: symptomatic infections (median [IQR] Ct: 16.3 [IQR 13.5–21.7]) compared to asymptomatic infections (Ct: 20 [IQR 14.5–29.5]). Previously infected persons tend to have a lower viral load (higher Ct values) than seronegative persons or vaccinated persons:

- Regev-Yochay et al find for health care workers (vaccinated and unvaccinated) a mean Ct value of 21.7 for symptomatic cases and 25.8 for asymptomatic cases.

Proportion of symptomatic Patients

The proportion of symptomatic patients is likely subject to various factors such as the SARS-CoV-2 variants present and the climate conditions. Therefore the dates and locations are stated from which both the variants prevalent and the climate conditions can be inferred.

Early 2020

The symptomatic proportion of cases varied through back since early 2020:

- Adam et al observe that until 27 March 2020 nearly everybody was symptomatic. Then abruptly from 27 March onwards the proportion of asymptomatic cases increased to about 40 %. // This could be due to the lineages having the D614G mutation.

Early 2021

- During the third Covid wave in Israel peaking around mid January 2021 about Regev-Yochay et al about 60 % of unvaccinated and about 50 % of vaccinated persons are asymptomatic.

Spread by Symptom Status

Note: The strains prevalent during the time of investigation is relevant since strains can induce varying immune responses e.g. coronaviruses can diminish or activate the immune system.

- Adam et al found in January through April in Hong Kong 2020 only 2.2% of the infections (7 out of 309) were caused by pre-symptomatic people.

- Madewell et al find that in household settings symptomatic infectors cause about 3 times as many infections as pre/asymptomatic infectors.

Viral Load in Epidemiology

Viral Load Interpretation

Like infections with the other human coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 infections are not per se pathogenic just if SARS-2 replicates to very high numbers at the wrong locations. If SARS-2 viruses are causing uneasiness, one has the disease Covid-19. Very high numbers of viruses in the lungs can cause severe or even deadly pneumonia (Chapter Viral Load: section Viral Load in the Lungs). Coronaviruses in health and disease are discussed in the chapter Virobiota.

Limit of Detection

The detection limit is mostly due to technical limits and not that lower viral loads are not frequently. Low viral load cause only rarely a disease and so for disease diagnosis a limit of detection of 10^3 to 10^4 copies per milliliter (corresponds to 35 to 40 cycles for most apparatuses) is more than good enough. As noted, coronaviruses living as commensal microorganisms in the human respiratory tract in healthy state are usually low in numbers and therefore only detected with a low probability. Some note on PCR accuracy in the chapter PCR Diagnosis. The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infections with a focus on disease causing infections is discussed in the chapter Diagnosis.

Viral Load Distribution

The viral load of a population sample has a continuous distribution. In practice the viral load is measured by methods such as PCR tests or antigen tests. These tests have detection limit above which the values are truncated. The viral load distribution obtained from ct values is thus chopped of at low viral load values (high Ct values) (Viral Load from Ct values). For similar reasons, since each viral load measurement has an error associated, low viral load values can pass as false negatives. The tests methods are mainly constructed to diagnose diseases and a disease is usually associated with high viral loads. Therefore these effects are mainly observed when diagnosing asymptomatic infections. In people with an early and good immune response (e.g. young people or people with a adequate immunization) the immune system restricts the growth of the viruses early and accordingly the viral load distribution are shifted towards lower values. These low viral loads usually don’t cause a disease.

Viral Load from Ct Value

The distribution of the Ct values often looks left skewed with many increasing frequencies towards higher Ct values and towards the PCR cutoff the distribution then sharply decreases towards the Ct value detection limit. This is not reflecting the actual viral load distribution since towards the detection limit the PCR sensitivity decreases which causes the Ct distribution to be increasingly chopped off at high Ct values. The actual distribution just continues below the LOD and then gradually decreases.

Viral Load Distribution and Positivity Rate

Explorative section.

Considering the unbounded viral load distributions, the PCR cutoff values such as 30, 35 or 40 PCR cycles are just arbitrary cutoffs and yield the number of samples below these values. So a positive test defined by 30 cycles - say 10^6 copies/milliliter - just detects all samples with a higher viral load. When close to the border, each samples is not detected with a certain probability due to the PCR error rate (PCR Diagnosis).

Hypothesis

There is a 1 to 1 correspondence between a shift of the viral load distribution and the probability of samples being above or below a certain threshold value as long as the shape of the distribution remains invariant (the true viral load distribution not the Ct value distribution).

In practice the distribution shape may slightly change, so the correspondence is only approximate.

Specifically, if an immune protection shifts the viral load distribution to lower values at a given location, the positivity rate is reduced and the other way round. E.g.:

- If natural immunity reduces the viral load, it reduces the chance for a positive test (can be a PCR test with a cutoff of 30 or 40 as described in Viral Load Shift by Immunity).

- Accordingly for vaccination: If vaccines fail to shift the viral load towards lower values the vaccines have no effects on testing positive at the given location => If vaccinated persons have about the same viral load distribution as unvaccinated persons, the vaccines do not offer a protection for infection at the location the viral load is measured.

The above effects are observed by analyzing members of Maccabi Healthcare Services (MHS): Levin-Tiefenbrun et al where in the first 2 months vaccination reduces a decrease viral load, whereas after 4 months vaccination by BNT162b2 results in nearly no reduction of viral load. Accordingly Mizrahi et al observe that the protection from vaccination decreases each month and seems to vanish about 4 to 6 months post vaccination (also noted in Comment on Protection decrease).

Viral Load Distribution Shifts

Viral Load Shift by Immunity

The same effect how the building up the vaccine immunity shifts the viral load distribution is also observed by Regev-Yochay et al when the vaccine induced immunity builds up (fully vaccinated is 10 days after the 2nd dose) in their cohort of hospital staff. According to the distribution shift, the detection rates decrease respectively the protection rates for CT values below 30/40 gradually increase:

| Status | mean Ct | reduction mean Ct | reduction Ct<40 | reduction Ct<30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unvacc | 22.2 | 0 (ref) | 0 % (ref) | 0 % (ref) |

| early vacc | 24 | 1.8 | 29 % | 45 % |

| part. vacc | 25.8 | 3.6 | 55 % | 59 % |

| fully vacc | 27.3 | 5.1 | 66 % | 70 % |

As of 28.1.22, the mean Ct values are roughly read from Fig. 3. in the paper. //For a couple of weeks (until 28.1.22) the mentioned Fig. 3 was displayed above, but since the license is CC BY-NC-ND (and not open access by CC BY as I previously thought) it is currently not shown anymore. For the time being only CC BY graphics are shown on this page.

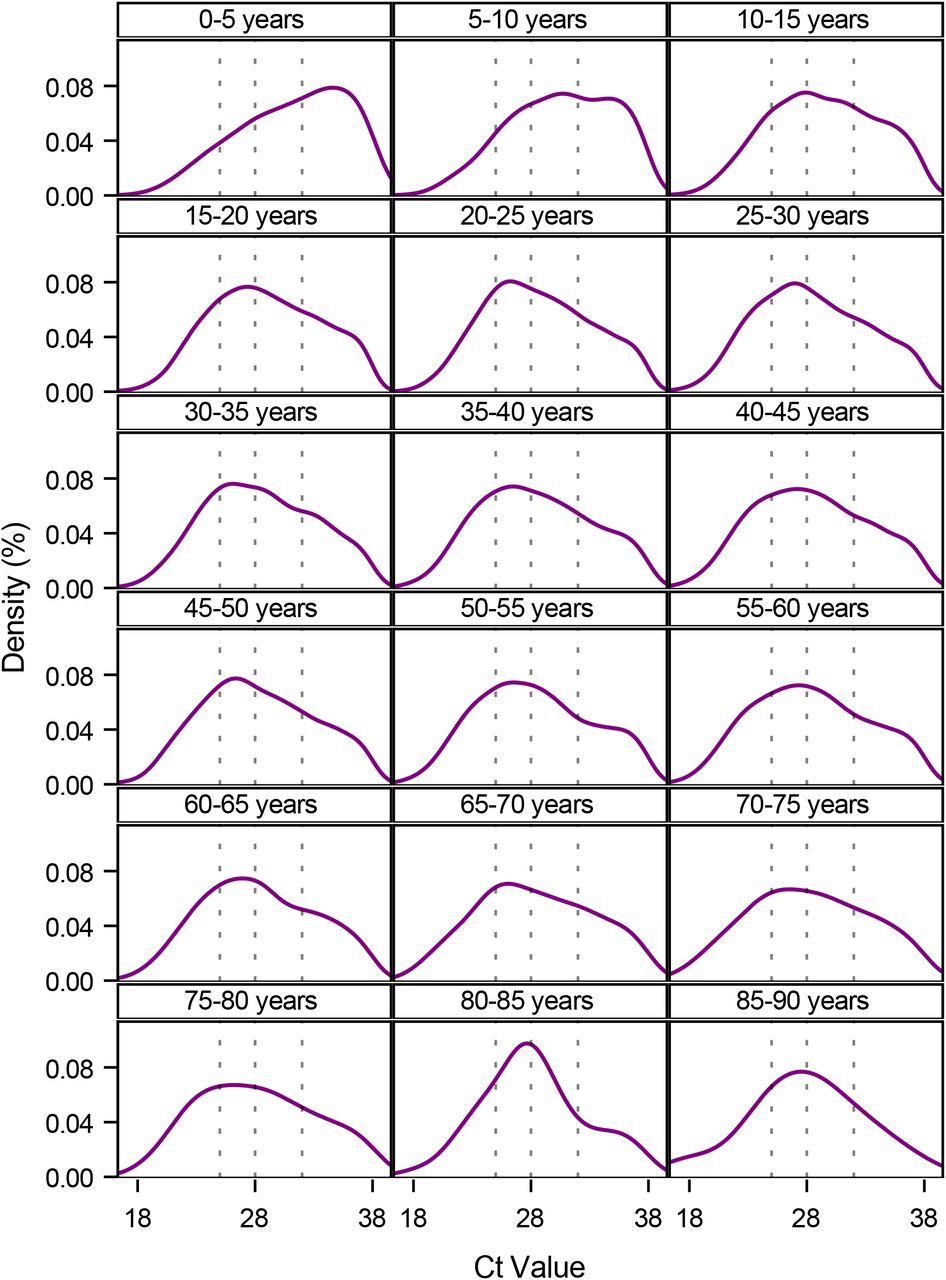

Viral Load Shift by Age

A shift in the viral load distribution is observed for different age groups. The graphics below, by Lyngse et al, visualizes the viral load distribution for different age groups. For children from 5 to 10 years the CT values plots are shifted towards higher CT values. From 10 to 20 there quite a lot of variation in the viral load and still many values towards the cutoff boarder indicating that many individuals have viral loads which are not reliably detected. For people above 80 years the viral load distribution is more centered.

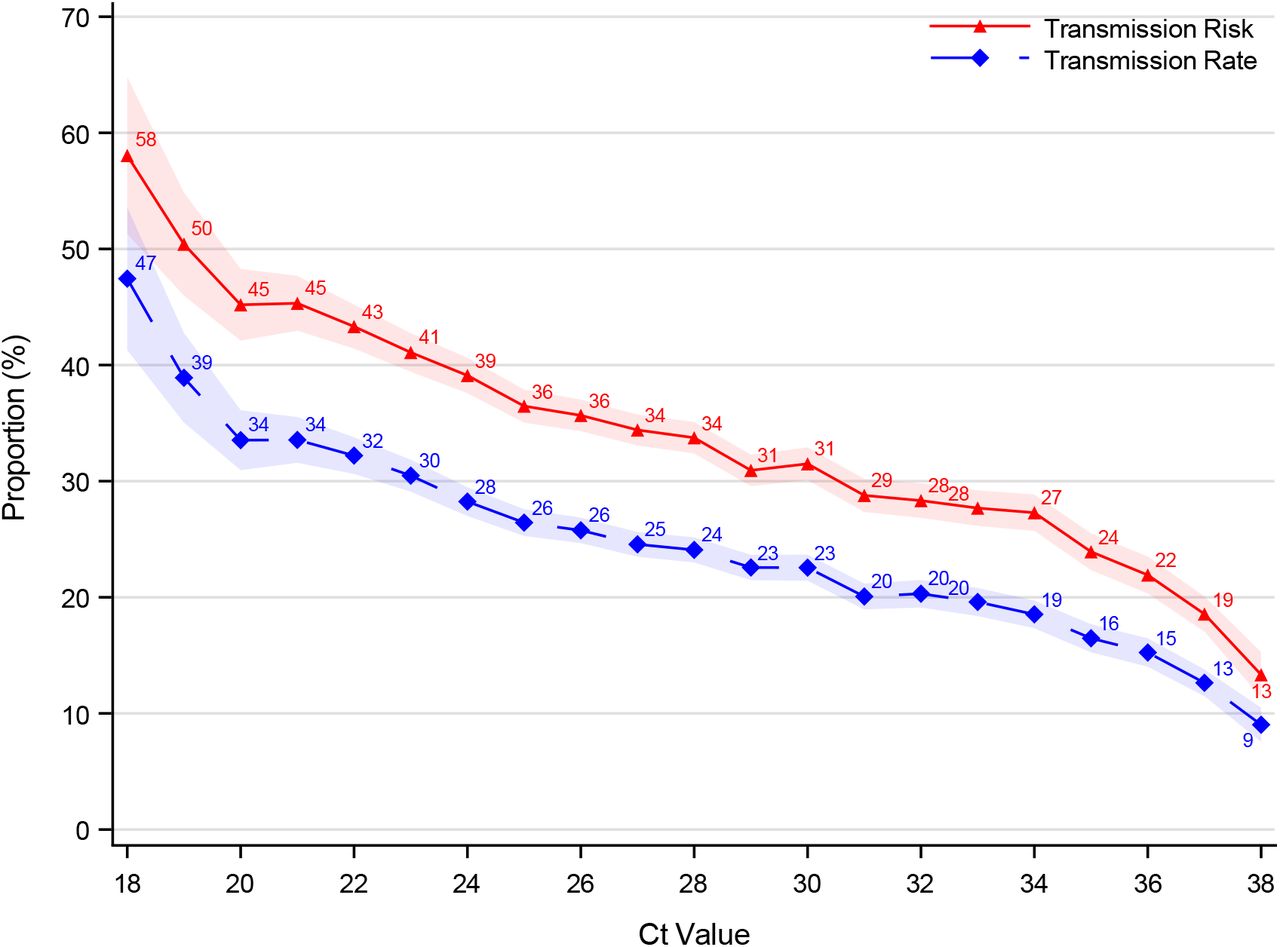

Spread by Viral Load

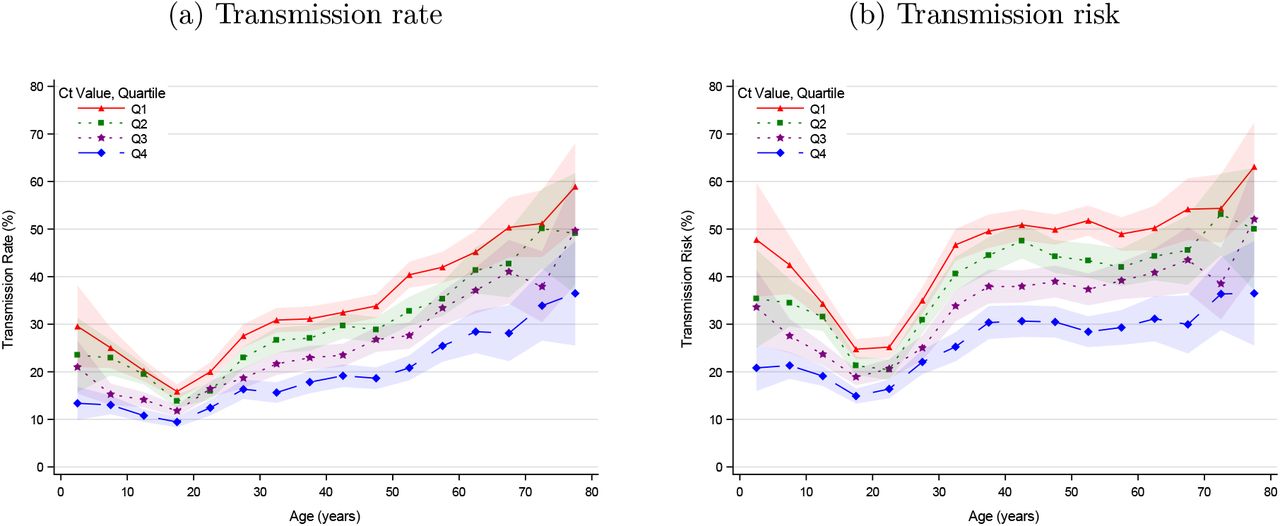

How many virions are at the different locations in the respiratory tract and how much particulates are exhaled from each location determine the amount of virions exhaled. The number of exhaled viruses is a major determinant for transmission - however the viral load in the URT (e.g. nose) can be quite different from the number of exhaled virions (Chapter Viral Load: Viral Load in Exhaled Air). On average however the viral load in URT predicts transmission. The following graphics from Lynsge et al shows the household transmission risk and rate by the viral load (risk=at least one contact infected and rate=infected/exposed):

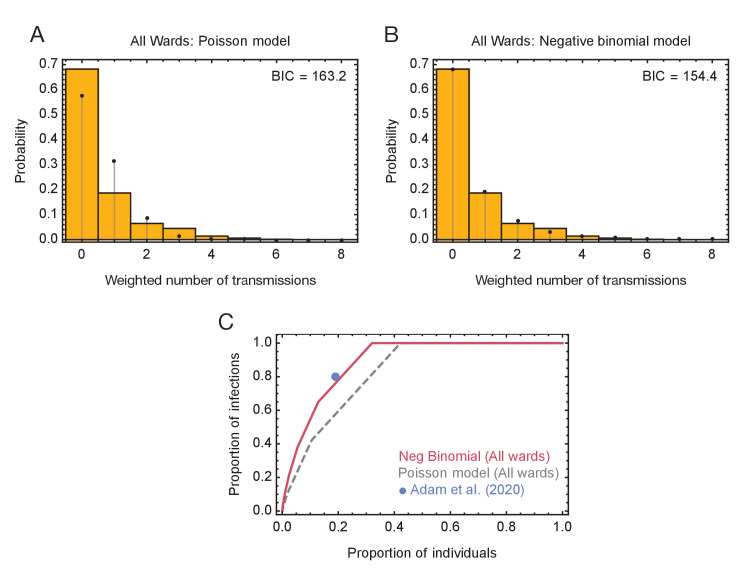

Infector Distribution

Observed Infector Distribution

The infector distribution is highly skewed:

- Contact tracing in Hong Kong revealed that Adam et al:

- 20% of the cases induced 80% of infections

- 10% of the cases induced 20% of infections

- 70% of the cases induced no observed infections (despite most of them being not in quarantine)

-

Illingworth et al analyse transmission in a hospital settings. They find that 10% of infectors cause about 50% of the infection and about 20% cause about 80% of the infections. Notably, most infections were caused by patients being treated in non Covid wards.

- A spread analysis (SEIR model based on sequencing and epidemiological data) in Israel in spring 2020 shows that between 2% and 5% of the population contribute for 80% of the spread (Miller et al). Comment: The simulation infers that if the actual cases were several fold higher than the actual cases, 2% of the population are responsible for 80% of the spread. This is likely the case since experience shows that even the best detection schemes miss the majority of cases.

Possible Causes for uneven Spread

Possible Biological Causes

- Individuality of SARS-CoV-2 Infections

SARS-CoV-2 infections are highly individual and situation specific.

- One reason is the immune system which in turn is influence by age and the associated exposure to pathogens. Young people tend to have a strong innate immune system which prevents SARS-CoV-2 to replicate to high numbers. The immune system of adults however, relies more on the acquired immunity from previously encountered pathogens. If a good immune response is not fast enough, in the big surface of the lower respiratory tract SARS-2 can replicate to high numbers. High viral in the lower respiratory tract can cause super spreading and severe Covid.

- Situation specific Transmission: In the lower respiratory tract the immune system can control viruses less well. Dry particulates enter the lungs well and accordingly most spread of severe Covid is in dry air.

- Individuality of Respiratory Tract Particle Shedding: Viral shedding is highly individual. Being infected does not imply one sheds infectious virions. The viral shedding depends on where the infection is, the respiratory behavior (e.g. breathing pattern, coughing, sneezing) and the physiology of the respiratory tract. How many small particulates persons produce is highly individual and tends to increase with age, male sex and BMI. Described on in particle sources. Other factors such as immune system preparedness and behavior are also important.

Possible Social Causes

- Socioeconomic conditions: Living Conditions influence transmission chains: People with small living space or small income have higher average R values.

- Behavior: How people behave is different.

- Some might notice symptoms, some not. Symptoms can be wrongly attributed to something else.

- For some it is easy to adapt the behavior and take precautions, for some it is not.

Effects of Movement

People with regular movement are less likely for a symptomatic disease. Additionally if positive or symptomatic, the risk for severe disease and hospitalization is reduced as outlined in the chapter Movement.

Associations to BMI

Geographical Observations of High Overweight Prevalence

High Overweight Prevalence is associated to High Covid Prevalence and Death Rates

-

Observations: Countries with high rates of obesity tend to have much more severe cases than countries with lower rates but otherwise similar characteristics.

Selected countries with high rates of obesity (in decreasing order, source: obesity.procon.org): US, Jordan, Turkey, Mexico, UK, Hungary, Israel, Czechia

Few obesity: Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Japan

-

Possible Explanation:

- One reason is for the many severe cases, is that obesity itself increases the risk for severe Covid. But the case counts seem to increase overall i.e. also in people which are not obese [to check and cite/provide evidence].

- A possible biological explanation is that the mucus clearance is inversely proportional to the BMI which increases susceptibility for infection and the risk for a high viral load (some notes in Increase the Mucus Flow). High BMI also increases the exhaled aerosol (chapter Particles in the Respiratory Tract).

Effects of Dirty Air Exposure

In short: Dirty Air Exposure is associated to a high Prevalence of Severe Covid.

Air Pollution

Through Air Pollution: High rates of air pollution occur frequently in industrialized densely populated regions which have inversion weather situations (usually in the winter). Examples (order: most polluted air first, source: estimates from watching the maps at ventusky.com): northern India, central and northern China (including Wuhan), northern Italy, Tehran

Specifically for Italy a correlation between Covid and air pollution is shown by Kotsiou et al.

Smoking

Through Smoking: Smokers and Ex-Smokers. Ex-smokers have a higher risk for severe risk than never smokers. For current smoker the risk is similar or only slightly higher than for never smokers.

- Simons et al is a meta analysis with studies from across the world.

The overall health benefits of a smoke stop outweigh by fare a possible increased Covid incidence: Current smokers seem to have no higher Covid risk than never smokers, but a lower risk than former smokers. This could be caused by (possibly toxic) environment changes in the lung when smoking. Local environment changes in the lungs can also be achieved with sauna or steam inhalation which don’t have the possibility of health hazards which smoke has.

12.6.21: It’s not about smoke-free - Everyone should judge the risks to take in life on his own.

Add restrictions for addictives, I consider as adequate however. Once in, getting or staying away is not always easy …

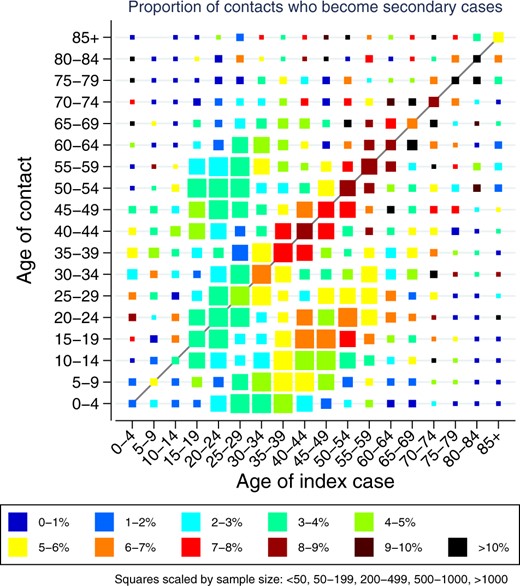

Transmissions by Age

Household Transmission by Age

Household Transmission in the UK

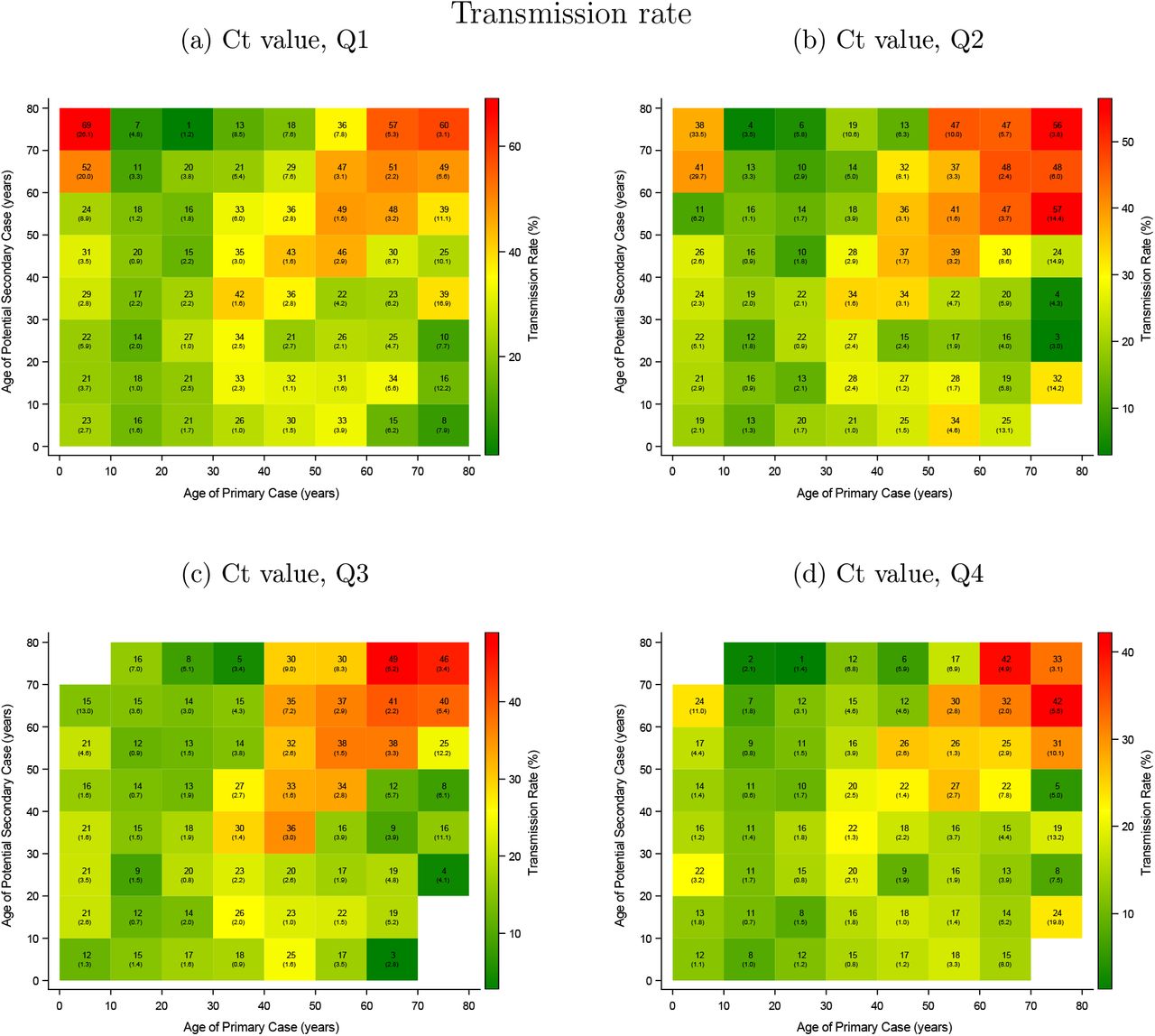

JA Hall et al reveal by analyzing “Household Transmission Evaluation Data” in England:

- people between 5 and 29 years have lower household transmission rates than the other groups.

- The household transmission is high between people over 40 years of approximately the same age.

- Very young children (0 to 4 years) transmit Covid frequently to their parents or grandparents.

Their immune system in the lungs is early in the training phase and additionally they may not have had contact with any coronaviruses and so they lack the cross immunity most older have acquired from the human endemic CoVs.

The observed transmissions by the age of the index cases (x-axis) and the contacts (y-axis) in households visualized (Figure 3 in Hall et al):

- A very similar transmission pattern is also observed in the Netherlands by van der Hoek et al. The transmission pattern shown in “Figuur” in their paper is very similar to the results shown above. The article is in dutch and for this reason is not considered any further.

Household Transmission in Denmark

Analyzing the household transmission by age is tricky, since older people often live in small households whereas children often in larger households. In larger households the attack rates (probability of infection) usually are lower e.g. there are usually several rooms. So in large household with children, an observed lower transmission rate, could be either due to the lower transmission rates of children or the larger household size. Lyngse et al tackle this, by defining the transmission risk as a least one transmission occurring and the transmission rate as the proportion of transmissions occurring. The transmission risk is excepted to be higher in larger households while the transmission rate is excepted to be higher in small households since in the latter people tend to be closer together.

Lyngse et al observe:

- Infants and young children:

- In the case of infants and young children the transmissions are low at low viral loads but increase with higher viral loads. However, as visualized in the section viral load by age in infants and young children a high viral load is rare.

- The transmission risk increases more than the transmission rate likely since they tend to live in larger households. Possibly, small children infect their mother but the risk siblings and father is likely lower.

- Teenagers and young adults are about half as infectious compared to people above 50. Even with high viral loads in the upper respiratory tract teenagers and young adults on average cause relatively few transmissions.

- With increasing age, the transmissions get higher. // The transmission risk plateaus from 40 to 60 likely since the household size decreases.

as visible from their graphics:

The transmission rate (left graphics above) from age to age for the different quartiles is visualized as follows by Lyngse et al.

As the graph above by Hall from the UK patterns but from Denmark and split into viral load quartiles; the color-scales vary and are bounded by the maximal values observed in each quartile.

Household Transmission in Israel

Dattner et al observe that children are relative to adults

- less susceptible 45% [40%, 55%]

- somewhat less infectious 85% [65%, 110%]

Household Transmission Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis by Madewell et al concludes that children are only about half as likely to get infected in households compared to adults (spouses are most likely to get infected, the adult infections are subject to relationship habits).

Susceptibility and Spread of Children

Transmissions in Schools

Children are less likely to be tested positive and less likely to be infectors. Children also do not super spread since in school settings no super spreading can be traced back to children - the super-spreading events observed, were likely caused by teachers.

A recommended review is COVID-19 Transmission and Children: The Child Is Not to Blame by B. Lee and W. Raszka.

- Vlachos, Hertegard and Svaleryd found that parents children in the 9th school year (open schools)had about the same incidence rate for Covid-19 as parents children in the 10th school year (closed school). If adjusted for factors such as age and occupation the risk was about 15% higher for being diagnosed with Covid-19 when the child went to open schools. // Comment: this indicate that other factors are more important than whether the children go to school.

- Large high school outbreak in Israel shortly after reopening of the schools. The outbreak was probably due to aerosol super-spreading from teacher(s) which was enable by densely populated rooms and the permanent use of air-conditioning Summary Stein-Zamir.

- Ehrhardt et al observed in Baden-Wuertenberg between 19 May to 28 July:

- 6 of 137 infected pupils infected a total of 11 other pupils (an R value contribution of below .1)

- 3% of infections of children (0-19 year) could be traced back to schools. Where as 41% to families and 8% to festivals/events.

- Perez-Lopez et al published statistics about viruses detected in nasopharyngeal swabs from visits in Sidra Medicine, the main pediatric center in Qatar. They observed a significant 30 fold reduction for influenza A. A 30% reduction was observed for influenza B and Common HCoVs. //Comment: Their observations indicate that in school settings only the influenza A transmission is efficient and other viruses are transmitted mainly in setting other than schools. This in turn indicates that most respiratory viruses are transmitted primarily by adults.

Susceptibility and Spread of Young Adults

- Reyes et al conclude by analyzing seroprevalences that no increased transmission occurs in student dormitories.

- In households setting young adults spread SARS-CoV-2 less than other age groups (Household Transmission by Age).

Biological Explanation for Age Effects

The immune system of young people is built to handle unseen viruses (Immune System throughout Life). For children SARS-2 is no more or even less dangerous than other respiratory viruses, it is just another new coronavirus. With increasing age the innate sensing mechanisms are diminished, which can give SARS-CoV-2 the opportunity to replicate to high numbers which in turn increases the probability for transmission and for severe disease.

Effects of Acquired Immunity

Effects of Natural Infection

Reinfection in Hospital Cohort Studies

- Lumley et al observe a protection of 85% against testing positive for staff in the Oxford Uni hospitals.

- VJ Hall et al observe a protection of 85% against testing positive at NHS hospitals in the UK.

Reinfection in Population Cohort Studies

- Chemaitelly et al find a protection of 92.3% (95% CI, 90.3 to 93.8) for the beta variant and a protection 97.6% (95% CI, 95.7 to 98.7) for the alpha variant in a case matched retrospective cohort study in Qatar.

- Hanson observe the following protection against reinfection in a national cohort study in Denmark:

- General population: 78·8% (95% CI 74·9–82·1)

- 65 years and older: 47·1% (95% CI 24·7–62·8).

- time (3–6 months of follow-up 79·3% [74·4–83·3], ≥7 months of follow-up 77·7% [70·9–82·9]

Vaccine Induced Immunity

Peak Protection of BNT162b2

The protection of BNT162b2 is highest from about 10 days after the 2nd does until about 6 weeks afterwards (depend several factors such as age and variants present) and then starts decreasing.

- Regev-Yochay et al find that for vaccinated persons the mean is about 22 and for unvaccinated about 27 Ct cycles NPS. The vaccine protection against is 66 % for a viral load <40 PCR cycles and 70% for a viral load <30 PCR cycles.

- VJ Hall et al observe that BNT162b2 provides protection of 75% against testing positive for SARS-2 in the staff of the UK NHS hospitals in about the first 6 weeks after the 2nd dose.

Vaccine Time Varying Effects

Building Up Vaccines Induced Immunity

The viral load viral load decreases (the Ct values increase) in a steady way with increased protection from vaccination (Maximal protection is achieved from about 10 days after the second dose). These effects are described in more detail in the section viral load shifts.

Waning of Vaccine Induced Immunity

[to be done] sweden study, us and israel

Vaccine Effects on Transmission

Covid vaccines usually reduce the probability to get infected. Some vaccines (depends on the vaccine and the virus type) also reduce the probability for ongoing transmission once infected.

Vaccines on the Transmission of SARS-CoV-2

The effect on vaccination on transmission is often analyzed in household settings. Another option is to analyse the effects of vaccination at a region level and check whether the case counts decrease.

Often vaccination is marketed as providing a very reliable immunity also against infection and transmission (Some countries even go as fare as to put restrictions on those not vaccinated). The supposed ‘safety’ can prompt relaxed precautions measures of those vaccinated, thus the protection can be underestimated in epidemiological analyses. However sometimes analyses seem to ‘assume’ a reduced transmission which can result in a biased analysis e.g. through adjustments.

- Singanayagam find that the SAR in household contacts exposed to fully vaccinated index cases was 25% (17 got infected of 69 exposed) and the SAR in household contacts exposed to unvaccinated index cases is 23% (23 got infected of 100 exposed). => Vaccines didn’t change transmission rates in households settings once infected. The vaccines did induce a slightly faster virus clearance however.

- Harris et al observe a reduction for 1 dose vaccinated index cases when the contacts are unvaccinated of about 40%. However when the contacts are also vaccinated there seems to be no reduction. The results thus are inclusive.

Vaccines on the Transmission for Measles and Small Pox

Measles and small pox vaccines reduce the ongoing transmission if a vaccinated index case gets infected despite vaccination. E.g. for measles by about 40% as observed by Cisse et al and for small pox by about 30% as observed by Mukherjee et al.

Vaccines on Shedding for Influenza A and B

Influenza A the vaccines do not to reduce viral shedding once symptomatically infected but even increase viral shedding as observed by Yan et al. Yan et al also observe that for influenza B the shedding is the same regardless whether vaccinated.

Comparing Vaccines and natural SARS-CoV-2 Infection

- Gazit et al use analyse data from a health care provider in Israel. Personsn with natural infection and vaccination before 28.2.21 were included (vaccination was December trough February and natural infections occurred mostly in a wave August through October 2020 and in one in January trough February 2021). Case matching results in 46035 persons per group. Using this model, natural infection resulted in a about 6 times higher protection against PCR positivity, about 7 higher protection against symptomatic infection and about 7 higher protection against hospitalization.

Overview of Data Sets

There are monitoring programs going on and the data acquired is often analysed in different studies regarding different questions. In the following an overview is given of a (subjective) collection of monitoring programs.

Population Infection Overviews

ONS-CIS

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the UK carries out a COVID-19 Infection Survey (CIS) where selected households take regular Covid tests.

- ONS-CIS dataset: Description of ONS-CIS followed by the references using this data.

- Prichard et al infer the risk of reinfection and the vaccine effectiveness from ONS-CIS data with data from 1st December 2020 to 8 May 2021.

- House et al analyse the household transmission with or without vaccination with data from 1st December to 31 May 2021.

- Pouwels et al is a continuation of the paper Prichard and analyse effects of natural and vaccine induced immunity on viral loads with data from 1st Dec to 1st August.

- Eyre et al analyse the impact of vaccination on transmission in households and from contact tracing.

HOSTED

Household Transmission Evaluation Dataset (HOSTED) links laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases in England to individuals living with the same address.

- HOSTED data set: Description of HOSTED data followed by the references using this data.

- JA Hall et al analyse the household transmission by the age of the individuals, the regions of living and the season of the year.

- Harris et al infer the household transmission with or without vaccination.

Hospital Cohort Studies

OUCS

Oxford University Hospitals offer symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 testing to all staff:

- References OUCS: OUCS testing methods followed by references using OUCS.

- Lumley December 20: Reinfection rates

- Lumley March 21: Reinfection rates and vaccine breakthroughs.

- Lumley July 21: Infection paths and spreader distribution.

SIREN

Goal: “The SARS-CoV-2 Immunity and Reinfection Evaluation (SIREN) Study is a large, multicentre prospective cohort study of health-care workers and support staff in publicly-funded National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in the UK.”

- SIREN: SIREN testing scheme followed by references using SIREN.

- VJ Hall April 21: Reinfection and vaccine efficacy.

Sheba Medical Center

- Regev-Yochay et al Ramat-Gan, Israel the effectiveness of BNT162b2 is evaluated.

Health Insurance Studies

- Maccabi Healthcare Services (MHS), Israel’s second largest Health Maintenance Organization analyses data from their members.

- Gazit et al compare the protection provided by vaccination and natural infections.

Spread from Contact Tracing

[in work]

References

References Spread Children and Schools

Alonso

Alonso, S., Alvarez-Lacalle, E., Català, M., López, D., Jordan, I., García-García, J. J., Soriano-Arandes, A., Lazcano, U., Sallés, P., Masats, M., Urrutia, J., Gatell, A., Capdevila, R., Soler-Palacin, P., Bassat, Q., & Prats, C. (2021). Age-dependency of the Propagation Rate of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Inside School Bubble Groups in Catalonia, Spain. The Pediatric infectious disease journal, 10.1097/INF.0000000000003279. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000003279

Lee,Raszka

Lee B and Raszka WV. COVID-19 Transmission and Children: The Child Is Not to Blame. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2):e2020004879 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-004879

Summary Ehrhardt,Brockmann

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in children aged 0 to 19 years in childcare facilities and schools after their reopening in May 2020 Ehrhardt J , Ekinci A , Krehl H , Meincke M , Finci I , Klein J , Geisel B , Wagner-Wiening C , Eichner M , Brockmann SO . , Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(36):pii=2001587. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.36.2001587

Methods

“We investigated data from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infected 0–19year olds, who attended schools/childcare facilities, to assess their role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission after these establishments’ reopening in May 2020 in Baden-Württemberg, Germany.”

School Setting

50% Group Size: Yes, Cleaning of Surface: Yes, Regular Ventilation: Yes, Hygiene: Yes, Face Mask in Break: Some, Face Mask in Classroom: No, Physical Distancing: Some, No Singing: Most, Physical Education: No

Results

- Infection by pupils

- Total of 557 Covid-19 cases in the age group 0-19 year out of a total of 3104 cases in Badenwuertenberg in the study period (19.5-25.7)

- For 453 School attendance information was available

- 137 (30% of 453) were at least 1 day at school while infectious

- 11 other pupils were infected by 6 of those 137

- no secondary infection from those 11 were detected despite extensive contact tracing

- only 15 (3%) of 453 infected children (with school attendance known) were infected in schools (the 11 above from other pupils and 4 by teachers). Most infections occurred in families or festivals/events (Table 2).

Summary Vlachos,Svaleryd

School closures and SARS-CoV-2. Evidence from Sweden’s partial school closure Jonas Vlachos, Edvin Hertegard, Helena Svaleryd

Methods

Remark: Working Paper

- “Swedish upper secondary schools moved to online instruction while lower secondary school remained open. This allows for a comparison of parents and teachers differently exposed to open and closed schools, but otherwise facing similar conditions.”

- the incidence rates were adjusted using logistic regression for wage, sex, occupation, educational attainment, income, regions of residence and of origin. OLS was used too.

Results

- Comparison of Covid-19 incidences between parents with children in schools and homeschooling:

- unadjusted the Covid incidence were near the same 5.67 versus 5.66 (Table 2)

- adjusted the risk for parents with children in school was about 15% [OR 1.15; CI95 1.03–1.27] higher if adjusted with logistic regression(Table 1)

- “Among lower secondary teachers the infection rate doubled relative to upper secondary teachers [OR 2.01; CI95 1.52–2.67]. This spilled over to the partners of lower secondary teachers who had a higher infection rate than their upper secondary counterparts [OR 1.30; CI95 1.00–1.68].”

Comment

It is not clear that the observed slightly increased Covid incidence of parents/teachers of lower secondary school children results from transmission from the children, it could also be attributed to parents visiting the schools and a transmission between adults.

Summary Stein-Zamir

A large COVID-19 outbreak in a high school 10 days after schools’ reopening, Israel, May 2020. Stein-Zamir Chen , Abramson Nitza , Shoob Hanna , Libal Erez , Bitan Menachem , Cardash Tanya , Cayam Refael , Miskin Ian . Euro Surveill. 2020;25(29):pii=2001352. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.29.2001352

Methods

Analyzing a large high school out break in Israel shortly after schools have been reopened.

School Setting

- From 13 March to 17 May Schools in Israel were closed (limited opening for small children on 3 May)

- A heat wave with temperatures up to 40 degree from 19–21 May:

- “air-conditioning functioned continuously in all classes.”

- no face-masks

- “crowded classes: 35–38 students per class, class area 39–49 m2, allowing 1.1–1.3 m2 per student”

Results

- “Testing of the complete school community revealed 153 students (attack rate: 13.2%) and 25 staff members (attack rate: 16.6%) who were COVID-19 positive.”

- “COVID-19 rates were higher in junior grades (7–9) than in high grades (10–12) (Figure 1). The peak rates were observed in the 9th grade (20 cases in one class and 13 cases in two other classes) and the 7th grade (14 cases in one class). Of the cases in teachers, four taught all these four classes, two taught three of the four classes and one taught two of these four classes.”

- “Most student cases presented with mild symptoms or were asymptomatic.”

Summary Dattner

Dattner I, Goldberg Y, Katriel G, Yaari R, Gal N, Miron Y, et al. (2021) The role of children in the spread of COVID-19: Using household data from Bnei Brak, Israel, to estimate the relative susceptibility and infectivity of children. PLoS Comput Biol 17(2): e1008559. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008559

Methods

- “Data were collected from households in the city of Bnei Brak (City close to Tel Aviv), Israel, in which all household members were tested for COVID-19 using PCR.”

- The authors developed a model (discrete, stochastic and dynamic) for the propagation of Covid within a households. With this model infectivity and susceptibility of children and adults can be estimated and compared.

Findings

- “Inspection of the PCR data shows that children are less likely to be tested positive compared to adults (25% of children positive over all households, 44% of adults positive over all households, excluding index cases), and the chance of being positive increases with age.”

- “We estimate that the susceptibility of children (under 20 years old) is 43% (95% CI: [31%, 55%]) of the susceptibility of adults. The infectivity of children was estimated to be 63% (95% CI: [37%, 88%]) relative to that of adults.”

References OUCS

Testing Scheme OUCS

OUCS = Oxford University Cohort Studies

Oxford University Hospitals offer symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 testing to all staff at 4 hospitals and associated facilities in Oxfordshire, United Kingdom:

- Test Methods:

- Acute Infection: nasal and oropharyngeal swab PCR testing

- Past Infection: Antibody status by anti-trimeric spike IgG ELISA

- Testing Frequency for acute Infection:

- Asymptomatic HCWs: voluntary PCR testing every 2 weeks and serological testing every 2 months

- Symptomatic: SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing for symptomatic (new persistent cough, fever ≥37.8°C, anosmia/ageusia)

Summary Lumley December 20

Lumley, S. F., O’Donnell, D., Stoesser, N. E., Matthews, P. C., Howarth, A., Hatch, S. B., … & Eyre, D. W. (2021). Antibody status and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(6), 533-540.

Lumley March 21 is a continuation of this study.

Methods and Setting

“A total of 12,541 health care workers participated and had anti-spike IgG measured; 11,364 were followed up after negative antibody results and 1265 after positive results, including 88 in whom seroconversion occurred during follow-up.”

Results

- 223 anti-spike–seronegative health care workers had a positive PCR test (1.09 per 10,000 days at risk), 100 during screening while they were asymptomatic and 123 while symptomatic.

- 2 anti-spike–seropositive health care workers had a positive PCR test (0.13 per 10,000 days at risk), and both asymptomatic.

- “After adjustment for age, gender, and month of testing (Table S1) or calendar time as a continuous variable (Fig. S2), the incidence rate ratio in seropositive workers was 0.11 (95% CI, 0.03 to 0.44; P = 0.002).”

Summary Lumley March 21

Lumley, S. F., Rodger, G., Constantinides, B., Sanderson, N., Chau, K. K., Street, T. L., … & Coward, G. (2021). An Observational Cohort Study on the Incidence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection and B. 1.1. 7 Variant Infection in Healthcare Workers by Antibody and Vaccination Status. Clinical Infectious Diseases.

Methods

- Data Observation Duration: March 2020 to 28.2.2021

- Analyse the effect of seroconversion due to natural infection and vaccination on infection rates as part of the OUCS testing.

- “Although an unexpected rise in incidence was seen in the first 2 weeks postvaccination, this time period was excluded from effectiveness calculations.”

Settings

- “As previously reported [2], asymptomatic testing was less frequent in unvaccinated seropositive HCWs (127/10 000 person-days) than unvaccinated seronegative HCWs (185/10 000 person-days). Rates in previously seronegative and seropositive vaccinated staff were similar (163–169/10 000 person-days). Symptomatic testing followed a similar pattern (Supplementary Table 1).”

- “Most HCWs were vaccinated between December 2020 and January 2021 (Figure 1A); 8285 staff received Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (1407 two doses) and 2738 Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine (49 two doses).”

Results

Incidences Rates

| Group | case count | adjusted incidence ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| seronegative HCWs | 635 | ref | - |

| unvaccinated seropositive HCWs | 12 | 0.15 | .08–.26 |

| seronegative, 1 dose vaccine vaccination | 64 | 0.36 | .26–.50 |

| second vaccination | 2 | ~ 0.10 | .02–.38 (large interval since only 2 cases) |

Comments:

- Very low person count for double vaccinated, thus the result has a large confidence interval.

- An increased infection risk in the first 2 weeks after vaccination especially for AstraZeneca

This can be due to behavior changes but in theory also biological mechanisms are thinkable e.g. vaccines can (temporarily) diminish the immune system by killing immune cells or the immune system is distracted: it builds up a strong immune protection against the vaccine and thereby temporarily ignores the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- From two weeks on after the first vaccine dose the rate of PCR positivity was reduce by about 65% (as described in incidence rates). The reduction was similar for BT162 and AstraZeneca. (Figure 3 )

[todo add figure 3]

Viral Load

- By Symptom Status: The median viral loads were higher, that is, lower Ct values lower in symptomatic infections (median [IQR] Ct: 16.3 [IQR 13.5–21.7]) compared to asymptomatic infections (Ct: 20 [IQR 14.5–29.5]) (Figure 4A, Kruskal-Wallis P < .001).” // since many asymptomatic individuals had low viral loads but high viral loads were observed in both groups.

- By Immune Status: “Unvaccinated seronegative HCWs had the highest viral loads (Ct: 18.3 [IQR 14.0–25.5]), followed by vaccinated previously seronegative HCWs (Ct: 19.7 [IQR 15.0–27.5]); unvaccinated seropositive HCWs had the lowest viral loads (Ct: 27.2 [IQR 18.8–32.2]) (Figure 4B, overall P = .06).” // only few cases of unvaccinated seropositive

Summary Lumley July 2021

Lumley, S. F., Constantinides, B., Sanderson, N., Rodger, G., Street, T. L., Swann, J., … & Eyre, D. W. (2021). Epidemiological data and genome sequencing reveals that nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is underestimated and mostly mediated by a small number of highly infectious individuals. Journal of Infection, 83(4), 473-482.

Methods

- Algorithm: The Covid spread is analyzed using contact pattern and genome sequencing.

- Setting: “The Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust comprises four hospitals with ∼1100 beds (mostly in 4-bed bays within wards of 20–30 beds) and ∼13,500 staff.”

Results

- Most introduction didn’t induce further transmissions: “Within 764 samples sequenced 607 genomic clusters were identified (>1 SNP distinct). Only 43/607(7%) clusters contained evidence of onward transmission (subsequent cases within ≤ 1 SNP)” // SNP = Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- “Most (80%) nosocomial acquisition occurred in rapid super-spreading events in settings with a mix of COVID-19 and non-COVID- 19 patients.” // The spread networks are shown in Figure 2 B. The hospital introductions and the onward spread in Figure 3.

References SIREN

Siren overview: Staff in publicly-funded National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in the UK.

Testing Scheme

“SIREN participants had asymptomatic PCR testing (anterior nasal swabs or combined nose and oropharyngeal swabs) every 14 days and monthly antibody testing at their site of enrolment, with a variety of assays used across sites. As per government guidelines, hospitals introduced twice weekly asymptomatic testing using a lateral flow device, Innova SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Rapid Qualitative Test (Innova),12 to all front-line health-care workers for twice weekly asymptomatic testing in November, 2020.”

Summary VJ Hall April 21

Hall, V. J., Foulkes, S., Saei, A., Andrews, N., Oguti, B., Charlett, A., Wellington, E., Stowe, J., Gillson, N., Atti, A., Islam, J., Karagiannis, I., Munro, K., Khawam, J., Chand, M. A., Brown, C. S., Ramsay, M., Lopez-Bernal, J., Hopkins, S., & SIREN Study Group (2021). COVID-19 vaccine coverage in health-care workers in England and effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection (SIREN): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet (London, England), 397(10286), 1725–1735. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00790-X

Methods

“Baseline risk factors were collected at enrolment, symptom status was collected every 2 weeks, and vaccination status was collected through linkage to the National Immunisations Management System and questionnaires. Participants had fortnightly asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing and monthly antibody testing, and all tests (including symptomatic testing) outside SIREN were captured.”

Setting

“At least one dose of vaccine was given to 20641 (89%) participants by Feb 5, 2021; 19384 (94%) received the BNT162b2 vaccine and 1252 (6%) received the ChAdOx1 vaccine.” // both first and second doses (for those who got them) peaked in early January 21 (Figure 1) -> unvaccinated follow was mostly December to early January, while vaccinated follow was early January to 5. February; 94% BNT162b2

Results

| Immune Status | # PCR positives | Incidence per 10 K person days | Reduction to sero - |

|---|---|---|---|

| sero - | 902 | 20 | ref |

| sero + | 75 | 3 | 85 % (*) |

| 1 dose | 66 | 11 | 45 % (*) |

| 2 dose | 8 | 5 | 75 % (*) |

(*) Comment: The reductions given above are unadjusted (in the paper adjustments are done). Adjustments are tricky e.g. Illingworth et al observe the majority of transmissions in non Covid wards. Adjustment for month would be important since in December and January there were many more cases than in February (e.g. observed in Lumley) and double vaccinated persons were mainly followed from mid January onwards. Further considerations in Analyzing Incidence Rates.

Refs Household Transmissions

Notes on Household Transmissions

Even if the Covid prevalence is low, infected household members may community acquire the infection at the same event since the transmission is super-spreading-event driven and the disease onset can be hard to determine due to asymptomatic/low symptomatic cases and varying incubation times. Methods such as sensitivity analyses with varying the cut-off dates between symptom onsets can sometimes increase the confidence in the model used. If the community transmissions are high, the secondary attack rates needs correction for community acquired infections. Also commented at Summary Madewell].

Summary Madewell

Household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis of secondary attack rate Zachary J. Madewell, Yang Yang, Ira M. Longini Jr, M. Elizabeth Halloran, Natalie E. Dean medRxiv preprint https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.29.20164590, posted August 1, 2020.

Methods

Meta-Analysis of studies regarding the transmission dynamics of Covid-19 in household settings. Many different kind of studies are included:

- Covid diagnosis based on live tests (RT-PCR) or past infections with antibody tests, some studies included symptoms, a few studies do whole-genome sequencing, some studies are in settings (area and times) of high prevalence.

- The influence of the different factors (contact type, symptom status, adult/child contacts, sex, relationship to index case, number of contacts in household, …) is analyzed.

Comment

Studies from countries with high and very high Covid prevalence are included too, in these countries independent infections pathways for different household members are very likely and thus inferring the secondary attack rate from the prevalence in household members overestimates the secondary attack rate.

Findings

Secondary Attack Rates with different groups as infectors. The error rate is in brackets.

- household: 0.19 (0.4); family including non household contacts: 0.18 (0.5)

- symptomatic: 0.2 (0.6); pre- or asymptomatic: 0.07 (0.04)

Secondary Attack Rates with different groups as infectees. The error rate is in brackets.

- children: 0.16 (0.6); adults: 0.31 (1.2) // adults includes spouses

- spouse: 0.43 (1.6); other: 1.8 (0.8)

Proportion of households where a secondary transmission was observed:

- 0.32 (.025)

Comparison with SARS-1 or MERS:

- SARS-1: 0.06 (0.04)

- MERS: 0.035 (0.035)

van der Hoek

De rol van kinderen in de transmissie van SARS-CoV-2 Wim van der Hoek et al https://www.ntvg.nl/artikelen/de-rol-van-kinderen-de-transmissie-van-sars-cov-2/abstract

Allen

Allen, Hester, et al. “Household transmission of COVID-19 cases associated with SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (B. 1.617. 2): national case-control study.” The Lancet Regional Health-Europe (2021): 100252.

Summary Ng

Ng, Oon Tek, et al. “Impact of Delta Variant and Vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 Secondary Attack Rate Among Household Close Contacts.” The Lancet Regional Health-Western Pacific 17 (2021): 100299.

Stich

Stich, Maximilian, et al. “Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Households with Children, Southwest Germany, May-August 2020.” Emerging infectious diseases 27.12.

Refs Household Transmission Endemic CoVs

Monto

Monto, A. S., DeJonge, P. M., Callear, A. P., Bazzi, L. A., Capriola, S. B., Malosh, R. E., … & Petrie, J. G. (2020). Coronavirus occurrence and transmission over 8 years in the HIVE cohort of households in Michigan. The Journal of infectious diseases, 222(1), 9-16.

Methods

Around a 1000 individuals in Michigan were contacted weekly to report acute respiratory illnesses (two or more symptoms like cough, fever or feverishness, nasal congestion, chills, headache, body aches, and sore throat). Upon illness, nasal and throat swabs were taken and tested human coronaviruses (HCoV) types OC43, 229E, HKU1, and NL63. The participant were interviewed for the illness.

Results

- CoV were the causes of ARIs in about 10 to 15%.

- The secondary attack rate is about 10%.

- The incubation period is about 3 days.

Refs of Household Transmissions with HOSTED

HOSTED Testing Scheme

- “In brief, laboratory confirmed cases of COVID-19 in England which are reported to national laboratory surveillance systems(2) are linked to individuals who share the same address, using National Health Service (NHS) number and the Unique Property Reference Number (UPRN).” (Supplement to Harris)

- Institutional settings (using UPRN information) such as care homes, prisons, and households with more than 10 residents are excluded.

- “HOSTED includes individual-level socio-demographic data for cases and household contacts, including age, sex, and Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD); information on property type, confirmed cases using PCR-based SARS-CoV-2 through national reporting systems, and linked information on hospitalisation and mortality. The vaccination data include date and type (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 or BNT162b2) of first and second doses for all vaccinated individuals in the HOSTED dataset.” (Supplement to Harris).

Summary JA Hall

JA Hall, RJ Harris, A Zaidi, SC Woodhall, G Dabrera, JK Dunbar, HOSTED—England’s Household Transmission Evaluation Dataset: preliminary findings from a novel passive surveillance system of COVID-19, International Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 50, Issue 3, June 2021, Pages 743–752, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab057

Methods

- The Household Transmission Evaluation Dataset (HOSTED) links confirmed COVID-19 cases to individuals in the same household in England.

- “We explored the risk of household transmission according to: age of case and contact, sex, region, deprivation, month and household composition between April and September 2020, building a multivariate model.”

Results

The heat map (Figure 3 in the paper and displayed in the section transmission by age) shows the secondary cases by age of the index case and age of the contact. The figure shows:

- Few Spread: People younger than 30 year but older than 4 have few secondary cases (left third of the image except left most column).

- Much Spread:

- For index cases above 40 years the transmissions are high. The transmission rates peak at an age of about 65 years.

- Very young children 0 to 4 of age transmit Covid well and mainly to their parents and their grand parents (left most column).

- Parents between 40 and 59 transmit to older children (15-24) but the children not to them (hotspot at middle right, missing hotspot on the mirrored)

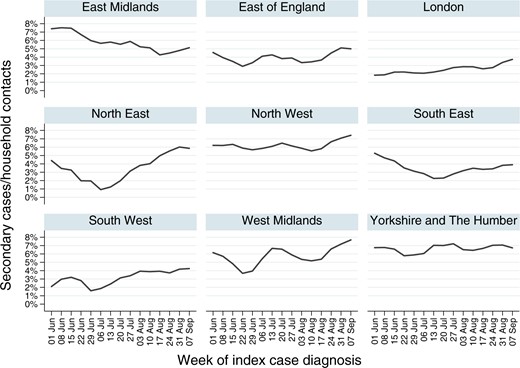

The graphs below show the secondary attack rate in the different administration division in the UK from June to early September 2020:

The Southern regions have lower secondary attack rates likely due to the more comfortable climate in the summer months.

Methods Details

“As the incubation period for SAR-CoV-2 is thought to be 2–14 days [16], we chose a threshold of 2 days between the specimen dates of the index and secondary cases as a pragmatic decision to offset the risks of misclassifying cases as either co-primary or as secondary. A sensitivity analysis using a cut-off of 4 days found to have little effect on any of the results or on the multivariable model. We have also made the implicit assumption that two (or more) cases occurring in a household within 2–14 days represents household transmission when it also plausible that they are two independent community-acquired infections. However, given the timing of this study, when the number of cases was at its lowest, this risk is probably small.”

// Simultaneous community acquired infection (e.g. at a super spreading event) cannot be ruled out even with the sensitivity analysis by varying the incubation cut-offs taking into account quite frequent asymptomatic/low symptomatic cases.

Summary Harris

Harris RJ, Hall JA, Zaidi A, et al. Effect of vaccination on household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in England. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2107717

Methods

- “The analysis cohort included households with an index case occurring between 4th January 2021 to 28th February 2021, with 14 days observable follow up for all contacts.”

- “We defined Index Cases as the earliest case of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, by diagnosis date, for a household. Household Contacts were defined as all individuals with the same address as the index cases of COVID-19; and Secondary Cases as a known household contact of an index case with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test that has a specimen date between two and 14 days after the specimen date of the index case.”

- “The analysis cohort included households with an index case occurring between 4th January 2021 to 28th February 2021, with 14 days observable follow up for all contacts.”

- “In all households, the majority of index cases and contacts were age <60, with a high proportion of individuals aged <40 in unvaccinated households.”

Results

- Index Non vaccinated: household attack rate is 10.1%: unvaccinated index cases induced 96,898 secondary cases out of 960,765 household contacts.

- Index vaccinated (21 days after first dose): household attack rate is roughly 6%: Index vaccinated with 1 dose ChAdOx1 induced 196 secondary cases in 3,424 contacts (5.72%). Index case 1 dose BNT162b2 induced 371 secondary cases in 5,939 contacts (6.25%). // not much difference between BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 this despite BNT162b2 initially offers a higher protection against infection.

- Index and (some) contact vaccinated: The secondary attack rate when both the index case and the contacts are vaccinated seems to be not much different as when both are unvaccinated: Secondary attack rate when both index and contact are vaccinated: 8152 out of 67622 contacts (Table S1) > SAR ~= 12%. The 12% SAR is about 60% of the attack rates of 19.6% observed between older couples (Table S4). Since vaccinated contact are less likely to get infected (though not necessarily all are vaccinated), this observation indicates no or only a slightly reduced transmission from vaccinated persons to other vaccinated persons once positive tested. // This calculation does not take days since vaccination into account (in the first 2 weeks after vaccination the infectivity seems to be stable for ChAdOx1 respectively to increase for BNT162b2 (Figure 2)).

=> The effect of vaccination on infectiousness is not quite clear. Comparing 1. and 2. indicates a reduced infectiousness by about 40%. However this could be influence by the decreasing incidence rates from January to February. The observations if both index cases and at least one contact is vaccinated in 3. indicates no much not much effect of vaccination on transmission if positively tested.

Comments

Adjustments: For the difficulties regarding correct adjustment, unadjusted data are stated above. This since adjusting is tricky: e.g. for older couples which belong to vaccine-prioritized groups, the secondary attack is higher, however in the weeks before a vaccination appointment the infection rate decreases in the UK as observed in Pritchard, and the latter is more likely in older couples (possibly due to increased care).

Biases: Vaccinated persons may be miss-classified as contacts since they are less likely symptomatic in the first month after vaccinations due to vaccine effectiveness at preventing symptomatic disease, placebo effects and the protection from severe disease. Which could yield to a bias in households with many infectees: the index case can be wrongly attributed to an unvaccinated person. Considering only households where both index and contact are vaccinated is less biased in this respect, as noted in 3., this data indicates no reduced transmission of vaccinated index cases.

Refs ONS-CIS Analyses

Households are visited and instructed how to self take nose and throat swabs. The household are visited weekly in the first month and then monthly for the first year. The swabs are sent or colleted and analyzed in labs for PCR testing. The goal overview of the community prevalence. From a random 10-20% of households, those 16 years or older were invited to participate in monthly antibody testing.

Summary House

House T, Pellis L, Pritchard E, McLean AR, Walker AS. Total Effect Analysis of Vaccination on Household Transmission in the Office for National Statistics COVID-19 Infection Survey. arXiv; 2021.

Goal

“Here we seek to calculate a total effect of having at least one completed vaccination in a household before introduction of infection, with no attempt to determine causation, mediation, confounding etc. We quantify uncertainty in the results using bootstrapping.”

Method Details

- “For visits to be included in the current dataset, participants had to be aged 16 years or over and have either a positive or negative swab result from 1st December 2020 to 31 May 2021.”

- “We did not differentiate between vaccines since our aim is to obtain a total effect of the programme as implemented.”

Results

- Households without vaccination: SAR = 23.5 [22.6,24.4]%

- Households with a least one vaccination 21 days before: SAR = 12.5 [4.0,23.3]% //the vaccination can either be the index, any contact, or all/both

Summary Pritchard

Pritchard, E., Matthews, P.C., Stoesser, N. et al. Impact of vaccination on new SARS-CoV-2 infections in the United Kingdom. Nat Med 27, 1370–1378 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01410-w

Methods

- 1,945,071 Covid PCR tests from nose and throat swabs taken from 383,812 ONS-CIS participants between 1 December 2020 and 8 May 2021 are analyzed to assess the effects of vaccination and previous infections.

- Vaccines used are nearly exclusively BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1

Results

- Fig. 1 a: The vaccines reduce number of samples with very high viral loads. Natural infection does so even better.

- Fig. 2 d: The two dose vaccines and natural infection reduce the chance for a positive test for B117 by about 80 %.

- Fig. 3b:

- BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 show a very similar effectiveness at reducing the odds for a viral load Ct<40 and Ct<30. //follow up analysis (Pouwels) reveals that BNT162b2 has a higher initial effectiveness but then decreases faster. The similar effectiveness obtained here, could be due to earlier vaccinations with BNT162b2 and so the time spans since vaccination were longer.

- The odds of a viral loads Ct<30 are more reduced compared to Ct<40 more compared to unvaccinated persons: The odds start to decrease about one week after the first dose, are further reduce 21 days after the first dose and reach a reduction of about 0.3 for Ct<40 and a reduction of about 0.15 for Ct<30.

Walker

Walker, A. S., et al COVID-19 Infection Survey team (2021). Ct threshold values, a proxy for viral load in community SARS-CoV-2 cases, demonstrate wide variation across populations and over time. eLife, 10, e64683. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.64683

further discussed in PCR Accuracy

Summary Pouwels

Pouwels, K.B., Pritchard, E., Matthews, P.C. et al. Effect of Delta variant on viral burden and vaccine effectiveness against new SARS-CoV-2 infections in the UK. Nat Med (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01548-7

Methods

ONS-CIS data is analysed for the periods 1 Dec 2020 – 16 May 2021 (Alpha) and 17 May 2021- 1 August 2021 (Delta)

Method Details

“During the Alpha-dominant period from 1 December 2020 to 16 May 2021 (Figure S1), nose and throat RT- PCR results were obtained from 384,543 individuals aged 18 years or older (221,909 households) at 2,580,021 visits (median [IQR] 7 [6-8]), of which 16,538 (0.6%) were the first PCR-positive in a new infection episode. During the Delta-dominant period from 17 May to 1 August 2021, results were obtained from 358,983 individuals (213,825 households) at 811,624 visits (median [IQR] 2 [2-3]), 3,123 (0.4%) being the first PCR-positive. Characteristics at included visits are shown in Table S1.”

Results

“From 14 June 2021, after which >92% of PCR-positives with Ct<30 were Delta-compatible (Figure S1), differences in Ct values between those unvaccinated (median (IQR) 25.7 (19.1-30.8) [N=326]) and ≥14 days after second vaccination (25.3 (19.1-31.3) [N=1593]) had attenuated substantially (age/sex-adjusted p=0.35, heterogeneity versus Alpha-dominant period p=0.01), as had differences with those unvaccinated but previously PCR/antibody-positive (22.3 (16.5-30.3) [N=20]).”

Comment on Pouwels

The results obtained partly fail the Bias Tests: E.g. the protection from natural infection was about 10% higher for roughly one month earlier data period end (Pritchard)[todo: confirm and add values in results]. Also sometime the protection against Ct<40 is higher than the protection <30 thus the results should be considered with care. The seasonal and measure induced incidence shift of Covid in the UK combined with shifting immune status on visits (extended Data Fig. 3 Proportion of visits by exposure.) may be a reason.

Refs Maccabi Healthcare Services

Maccabi Healthcare Services (MHS), Israel’s second largest Health Maintenance Organization, with 2.5 million members (25% of the population).

Summary Gazit

Gazit, S., Shlezinger, R., Perez, G., Lotan, R., Peretz, A., Ben-Tov, A., Cohen, D., Muhsen, K., Chodick, G. and Patalon, T., 2021. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 natural immunity to vaccine-induced immunity: reinfections versus breakthrough infections. MedRxiv.

Methods

- Type: Retrospective cohort study with case matching analyzing data from members of MHS health care fund.

- Population: The study population included MHS members aged 16 or older.” //the different cohorts are described under models in the result section below

- Diagnosis: RT-PCR test and symptoms in the next 5 days (chiefly fever, cough, breathing difficulties, diarrhea, loss of taste or smell, myalgia, weakness, headache and sore throat.)

- Dependent Variables: “Outcomes, or second events: documented RT-PCR confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19, COVID-19-related hospitalization and death. Outcomes were evaluated during the follow-up period of June 1 to August 14, 2021, the date of analysis, corresponding to the time in which the Delta variant became dominant in Israel.”

Results

Three different comparison denoted as Model 1 (infected in early 2020 compared to vaccinated in early 2020), Model 2 (anytime infected compared to vaccinated in early 2020) and Model 3 (infected compared to infected and additionally vaccinated) are made.

The odds ratios below are adjusted for comorbidities and market with (*).

Model 1

Comparison of vaccinated persons (second dose between 1.1. and 28.2.21) to persons infected (SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR test between 1.1. and 28.2.21). A total of 16215 persons were in both groups.

| Outcome | outcome in vaccinated | outcome in recovered | odds ratio (*) | 95% confidence (*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive PCR | 238 | 19 | 13.06 | [8.08, 21.11] |

| Symptomatic Inf. | 191 | 8 | 27.02 | [12.7, 57.5] |

| Hospitalization | 8 | 1 | ~ 8 | too few cases |

Model 2

Comparison of vaccinated persons to infected any time before. Each of the two groups contained 46035 persons. Notes

- The difference to model 1 is that the natural infection was allowed to occur any time before 28.2.21. Most infections happened in September 2020, thus the natural infections occurred on average before the vaccination. The study population is more than 3 times as large.

- To check whether the Covid pass from natural infection was valid throughout the entire study period. //else the results could be “Covid certificate” biased, which could for example induce an overestimation of the vaccine efficacy compared to natural infection.

| Outcome | outcome in vaccinated | outcome in recovered | odds ratio (*) | 95% confidence (*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive PCR | 640 | 108 | 5.96 | [4.85, 7.33] |

| Symptomatic Inf. | 484 | 68 | 7.13 | [5.51, 9.21] |

| Hospitalization | 21 | 4 | 6.7 | [1.99, 22.56] |

Model 3

Comparison of immunity by natural infection alone and infection followed by vaccination (between March and 25.5.21). // the vaccination occurred right before the study period, thus this model 3 describes primarily whether an additional vaccine has an effect on reinfection in the first few months.

| Outcome | outcome in recovered and vaccinated | outcome in recovered | odds ratio (*) | 95% confidence (*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive PCR | 20 | 37 | 0.53 | [0.3, 0.92] |

| Symptomatic Inf. | 16 | 23 | ~0.7 | - |

| Hospitalization | - | - | - | - |

Summary Levine-Tiefenbrun

Levine-Tiefenbrun, M., Yelin, I., Alapi, H., Katz, R., Herzel, E., Kuint, J., … & Kishony, R. (2021). Viral loads of Delta-variant SARS-CoV2 breakthrough infections following vaccination and booster with the BNT162b2 vaccine. medRxiv.

Methods

- “In this study, we retrospectively collected and analyzed the reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR) test measurements of three SARS-CoV-2 genes - E, N and RdRp (Allplex 2019-nCoV assay, Seegene) - from positive tests of patients of Maccabi Healthcare Services (HMS). We focus on infections of adults above the age of 20 between June 28 and August 24, when Delta was the dominant variant in Israel (over 93%)36. Crossing this dataset with vaccination data, we identified in total 1,910 infections of unvaccinated, 9,734 BTI of 2-dose-vaccinated and 245 BTI of booster-vaccinated (Methods: “Vaccination status”, Extended Data Table 1).” //data by time after vaccination in Extended Data Table 1

- “Considering all of these infections (n = 11,889), we built a multivariable linear regression model for the Ct value of each of the three genes, accounting for vaccination, at different time bins prior to the infection, and for receiving the booster as well as adjusting for sex, age and calendric date.”

Results

Results are described in the text and shown in Figure 1 for RdRp gene and for the N and E gene in Extended Data Figure 1. The results for the different gene are consistent and similar.

- The viral load from 1 week after the second dose up to 2 months thereafter is reduced about 15 fold (Ci:4-53) which corresponds to a Ct value of 4 (this is consistent with the observations by Regev-Yochay et al where a reduction of 5 Ct values was observed).

- From 2 to 4 months the Ct values are reduced by about 0.7.

- From 4 to 6 months the Ct values are reduced by about 0.3.

- From 6 months onwards no relevant reduction is observed.

- A booster increases the reduction to about 2 Ct values. //mainly older people got a ‘booster’.

For people above 50 years:

Extended Data Figure 2.

- In the first 2 months the reduction of the Ct values is about 6.

- After 2 months there is no relevant reduction of Ct values.

The reduced shifts in viral load go in parallel to a protection decrease as noted in Comment to Mizrahi et al.

Summary Mizrahi

Mizrahi B, Lotan R, Kalkstein N, Peretz A, Perez G, Ben-Tov A, Chodick G, Gazit S, Patalon T. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2-breakthrough infections to time-from-vaccine. Nature communications. 2021 Nov 4;12(1):1-5.

Methods

“Leveraging the centralized computerized database of Maccabi Healthcare Services (MHS), we assessed the correlation between time-from-vaccine and incidence of breakthrough infection between June 1 and July 27, the date of analysis.”

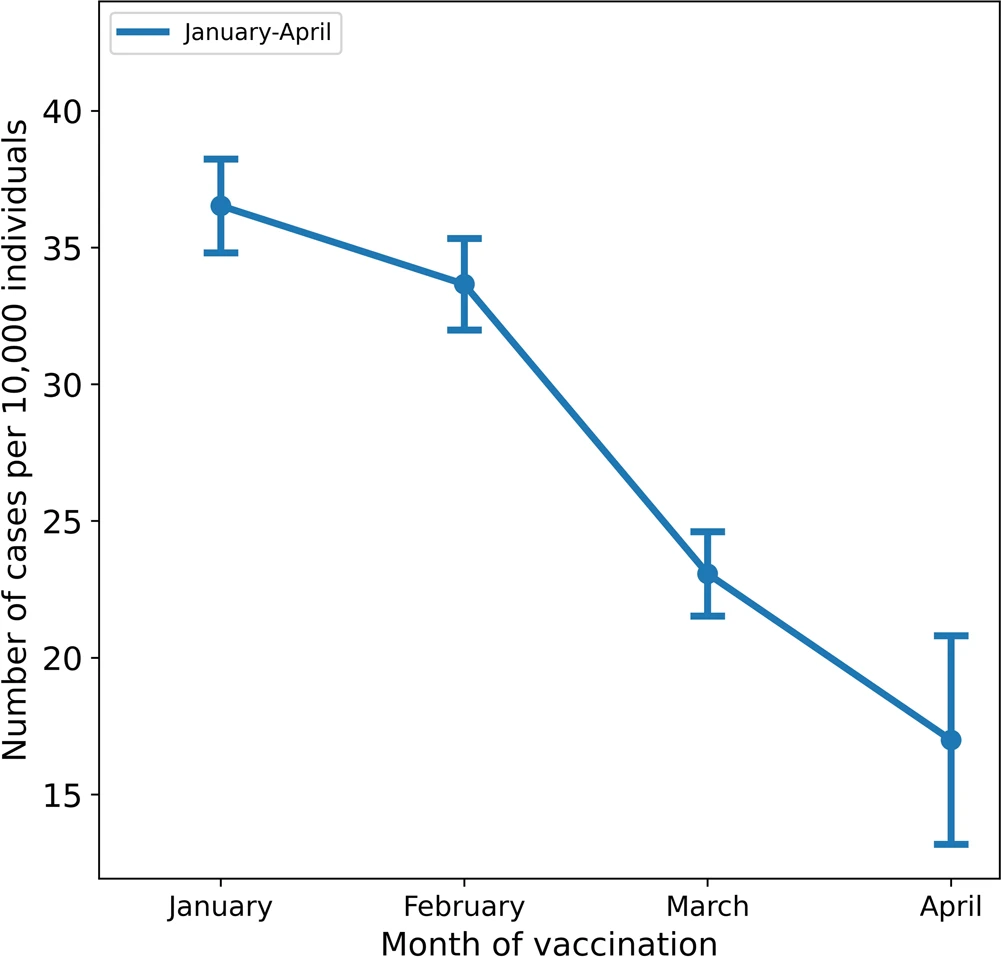

Results

Figure 1 shows the crude breakthrough infection rates per 10’000 individuals by month of vaccination:

Comment on Protection Decrease

Table 1 in the paper indicates that the change to get infected increases each month since vaccination by about a third = 33%. So 1 month: 1.33, 2 months: 1.77 and 3 months: 2.35 i.e. the hazard ratio is 1.33 when comparing 1 month difference and 1.77 when the difference is 2 months and 2.35 for 3 months. After 4 to 5 months this would yield an increase of 3.13 to 4.16. When the initially the hazard ratio compared to unvaccinated is 0.3 (as indicated by the data from Regev-Yochay et al) then after 4 to 5 months the protection is lost. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the vaccine are only efficient as long as they induce a shift towards lower viral loads since Levine-Tiefenbrun et al observe that there is nearly no reduction of viral loads after 4 months (Viral Load Shift and Positivity Rate Hypothesis).

Refs Cohort Studies

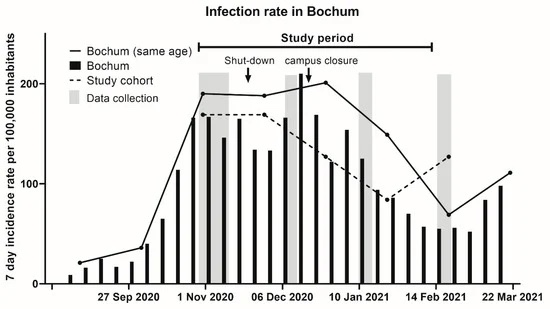

Reyes

Torres Reyes,C.R.; Steinmann, E.; Timmesfeld, N.; Trampisch, H.-J.; Stein, J.; Schütte, C.; Skrygan, M.; Meyer, T.; Sakinc-Güler, T.; Schlottmann, R.; et al. Students in Dormitories Were Not Major Drivers of the Pandemic during Winter Term 2020/2021: A Cohort Study with RT-PCR and Antibody Surveillance in a German University City. COVID 2021,1,345–356. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid1010029